My newly published paper on the relationship between creativity, innovation & novelty, generative AI/LLMs, future potentials, and the creative agency of the world:

Peschl (2024). Human innovation and the creative agency of the world in the age of generative AI. Possibility Studies & Society, https://doi.org/10.1177/27538699241238049 (online first, open access)

Abstract

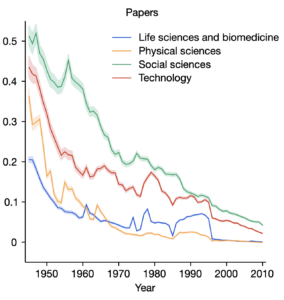

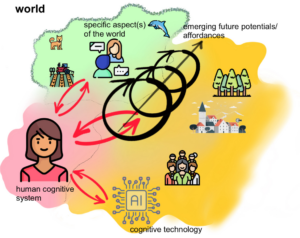

With the advent of Large Language Models, such as ChatGPT, and, more generally, generative AI/cognitive technologies, global knowledge production faces a critical systemic challenge. It results from continuously feeding back non- or poorly-creative copies of itself into the global knowledge base; in the worst case, this could not only lead to a stagnation of creative, reliable, and valid knowledge generation, but also have an impact on our material (and subsequently our social) world and how it will be shaped by these rather uninspired automatized knowledge dynamics.

More than ever, there appears to be an imperative to bring the creative human agent back into the loop. Arguments from the perspectives of 4E- and Material Engagement Theory approaches to cognition, human-technology relations as well as possibility studies will be used to show that being embodied, sense-making, and enacting the world by proactively and materially interacting with it are key ingredients for any kind of knowledge and meaning production. It will be shown that taking seriously the creative agency of the world, an engaged epistemology, as well as making use of future potentials/possibilities complemented and augmented by cognitive technologies are all essential for re-introducing profound novelty and creativity.

Keywords: AI, cognitive technologies, creative agency of the world, creativity, 4E cognition, embodied cognition, engaged epistemology, future potential, innovation, large language models, possibility, radical novelty, World

Download here: https://doi.org/10.1177/27538699241238049 (online first, open access)

#AI #cognitivetechnologies #creativeagencyoftheworld #creativity #4Ecognition #embodiedcognition #engagedepistemology #futurepotential #innovation #LLM #radicalnovelty