Joy @ Work — on the relationship between joy and work (in the 21st century)

This is part 2 of a first draft of an explorative paper on the relationship between joy/joyfulness and work.

The next parts will follow in the next blog entries

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

Joy and/at work

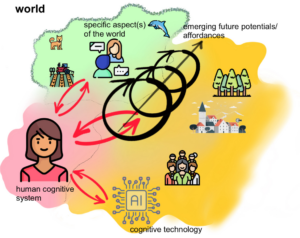

The activity of work(ing) is an intrinsic part of our human being (e.g., Arendt, 2001). It is about our capacity to design and shape (“gestalten”) the world (and being shaped by it). In other words, giving our world a shape according to and in co-operation/co-creation with our mind is an essential activity of the human person (“homo faber”). As is suggested by the 4E approaches in cognitive science (e.g., Newen, de Burin, and Gallagher, 2018; Hutto, Kirchhoff, and Myin, 2014) or by Material Engagement Theory (Malafouris, 2013, 2014, 2020) actively engaging with the world and enacting it is one of the key activities of a cognitive system. Work or art can be considered as behaviors that realize this engagement.

Vita contemplativa, vita activa, and vita automatica

While (non-intellectual) work was not highly valued in ancient Greece (political action had the highest value), this has changed dramatically since the beginning of modern times. The traditional hierarchy of vita contemplativa and vita activa (i.e., contemplation vs. action/theory vs. practice) was turned upside down (e.g., Arendt, 2001). Producing, making, and fabricating have become key characteristics of homo faber and enjoy highest priority and social recognition. Productivity, efficiency, optimization, and the principle of utility are the ideals and goals of working. It is no longer a purpose or usefulness (of an artifact or product/service) that counts, but it is productivity/work for the sake of productivity/work and, as a consequence, personal well-being experienced in producing and consuming.

This is especially true today for our capitalist, technology- and knowledge-driven society and economy. Division of labor as splitting and assigning different parts of a production process or task to different people in order to improve efficiency has led to losing purpose in the activity of working. In complex work environments, workers can no longer see and understand their particular contribution to the overall artifact, product, or purpose of the organization they work for. This alienation from purpose (e.g., Arendt, 2001; Smith and Fessoli, 2021) has increased even more in modern working environments that are driven by automation, hyper standardized and uniform work processes and workflows, excessive division of labor (e.g., in globally distributed value chains and production networks), as well as cognitive technologies reducing human original thinking to its minimum.

Far from eudaimonia, work and productivity have become ends in themselves. While contemplation is considered superfluous or even an obstacle to productivity, our most valuable human activities, such as cognitive processes, individual and original (deep) thinking, (participatory) sense-making, reflection, social capacities, etc. are outsourced to cognitive machines (Vidovic and Peschl, 2020). In some instances, they are even regarded as undesirable.

Will our future working society run out of work and purpose? For most persons whose work is still needed, work activities (have) become highly standardized, repetitive, specialized, etc. They become “human automata”. In other words, their working tasks and patterns will not contribute a lot to their self-actualization (rather to frustration or depression). In a future scenario (concerning the future of work and economy), „automation should be pushed “beyond the acceptable parameters of capitalist social relations” into a future of fully-automated luxury communism (FALC)… Accelerating automation provides the technological means for transcending contradictions already evident in capitalism… for moving automation over to a post-capitalist political economy better equipped to manage structural underemployment and unemployment, worsening ecological degradation, diminishing costs and falling profitability. FALC argues socialised automation will deliver an abundance of socially useful goods and services at diminishingly marginal cost. Automation will finally liberate people from labour and enable them to enjoy flourishing and meaningful lives. Abundant automated production provides the material basis for transforming ideas and expectations about work, income, leisure, and sustainability…” (Smith and Fressoli 2021, p 3) Universal basic income, reduction of working hours, an increase and shift to more personal development and fulfillment could be key ingredients of such a scenario. However, such a scenario in which (classical forms of) work will disappear has to be seen critically as well: it will not only have a crucial impact on the economy, but above all on a societal and personal level; “work” is one of the most fundamental activities of a human person and it is far from clear what could take its role (and how), if it is abandoned.

Only a very limited number of people will have the privilege to work in a job (in the classical sense) that offers them purpose and an opportunity for self-actualization, and that is intellectually and/or socially challenging and inspiring. Apart from jobs in the social, hospitality, and caring industry (which are in need of social, empathic, emotional, etc. capabilities and attitudes; Smith and Fressoli, 2021), these jobs will require highly sophisticated thinking/cognitive and creative skills (Frey and Osborne, 2013; OECD, 2021; World Economic Forum, 2020; BBVA Open Mind Book, 2019).

Work, eudaimonia, and re:creation

In contrast to an economy and social dynamics being primarily driven by efficiency, productivity, and speed that is induced mainly by automation and digital technologies, we propose an alternative approach to work and how to relate it to joy/eudaimonia. It makes use of the theoretical concepts having been discussed above and is compatible with a digital humanist approach (Doueihi, 2011; Peschl and Vidovic, 2020). Above that, it offers interesting new perspectives for the fields of knowledge work, creativity, and innovation.

In this context, we introduce the concept of re:creation. In its everyday meaning it denotes an activity that is done for one’s enjoyment, for instance, when one does not have to work. We propose to dig deeper, however, as there is much more to it than these aspects of wellness, pleasure, play, or entertainment (see our discussion above). Actually, going back to its Latin roots we can find some hints: re:creation is derived from the Latin word “recreare/recreatio”; “re-” is a prefix and means “again”; “creare” can be translated to create, bring forth, bring into being, beget, or give birth to. Etymologically speaking, recreare has various connotations, such as to restore, recover (from illness), refreshment of strength and spirits after work, to make new, or revive.

There is a clear relationship between re:creation and joy, leisure, and play. However, we do not want to limit our understanding of re:creation to well-being, relaxing, or just amusement. In the context of eudaimonia, creativity, and innovation, we want to focus on the aspects of renewal and bringing something to life, of bringing forth novelty, and of making something new as an activity that is not necessarily driven by and embedded in a paradigm of functionality and efficiency.

Going one step back further, brings us to the concept of leisure that is closely related to joy and re:creation; Aristotle describes it in an illuminating manner: “We should be able, not only to work well, but to use leisure well; for, as I must repeat once again, the first principle of all action is leisure. Both are required, but leisure is better than occupation and is its end; and therefore the question must be asked, what ought we to do when at leisure?“ (Aristotle, Politics 8 (3); italics by author)

The role of re:creation, joy, and leisure in the context of work

Aristotle makes an astonishing remark that might sound a bit counterintuitive for our time: he claims that we are working for the sake of leisure, and that leisure is the final cause of work. In a way he has reversed today’s order that—as we have seen above—is driven by the imperative of working for the sake of working and productivity. In such a context, leisure is reduced to a means for increasing our productivity in the domain of work (think, for instance, about work environments or coffee lounges that foster wellness at work, that invite for “informal” meetings, that are cosy, etc.). Leisure gets instrumentalized, it is no longer an end, but becomes a means.

Aristotle warns us that leisure should not be confused with amusement or „doing nothing“, however. Rather, as we have seen in our discussion above, he shows that leisure is related to a more contemplative activity, to eudaimonia. It is a „purposeless activity“ for the sake of itself leading to a state of internal rest, “contemplation”, or resonance with oneself. Prima facie, it is not instrumental. As an example, Aristotle mentions intellectual activities that are valued for themselves. In other words, leisure understood in such a sense does not (directly) aim for a “product”, an “outcome”, or some accomplishment in the first place. If something interesting or purposeful arises out of these activities this product or outcome should be considered rather as a “by-product”.

If we consider the focus of the future of work to be on high end, joyful and cognitive/knowledge work, creative activities, dealing with and bringing forth novelty, and on innovation, this has interesting implications for our discussion on the relationship between joy and work in the context of digital technologies and digital humanism. What Aristotle suggests is a change in attitude and mindset: intellectual work, creativity and creating novelty cannot only be brought forth through a purely functional and mechanistic regime. Rather, deep insights and novel knowledge have to be seen as a “by-product” that have emerged from a state of leisure or re:creation. It is not primarily the result of working for the sake of work. Leisure and contemplation are required for meaning-/purposeful work/occupation in order to bring about a meaningful world.

Evidence from cognitive/neuro-science

Such a perspective does not only have support from classical philosophy, but also from recent findings in neuroscience and cognitive science. Just to name a few, there is evidence that creativity has its roots in resting states and meditative activities (Tang et al. 2015), or that creativity emerges from a subtle oscillation between divergent and convergent thinking, between conscious and unconscious brain processes and relaxed brain states (Maldonato et al. 2016; Dietrich & Kanso 2010), or that the level of creative problem solving is increased in natural and silent environments (e.g., Attention Restoration Theory and activation of default mode networks that are active during resting; Atchley et al. (2012)), etc.